Wordle is kinda old news at this point, but I’m still deeply invested. I play every-ish day, and it’s a nice ritual. It also continues to be a gold mine for accessible information theory problems. More than anything, I think a lot about the little copy-paste results that you post on twitter or send to your mom or whatever. There’s one specific problem that I’ve been thinking about since December that I’m excited to share about today. For this post, I’ll assume that you are very familiar with the rules and strategy of Wordle.

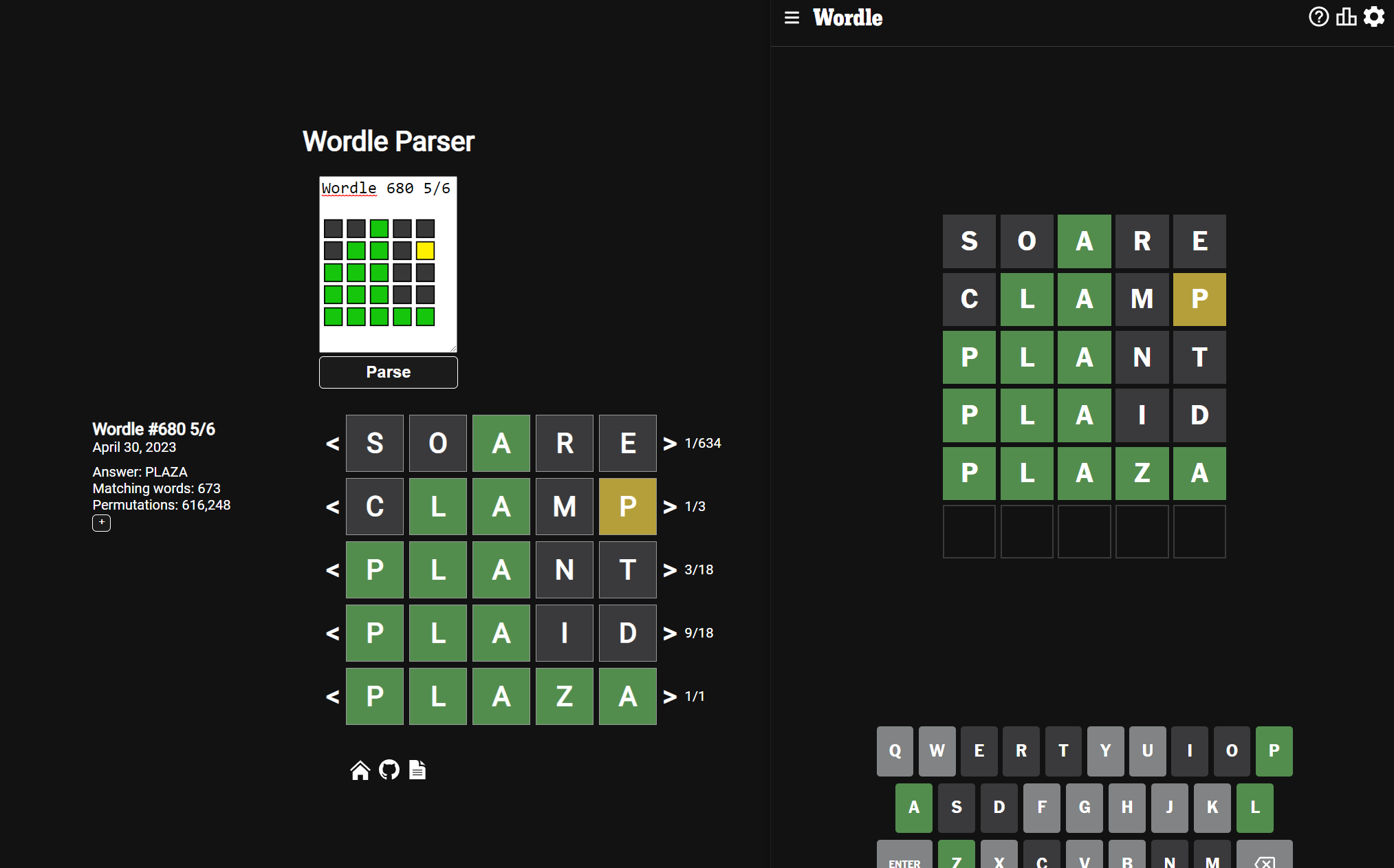

Here are my results from today:

Wordle 680 5/6

⬛⬛🟩⬛⬛

⬛🟩🟩⬛🟨

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Imagine I texted this to you — you are now challenged to beat my 5/6 score. What information could you draw from this blurb to give yourself an unfair advantage? After some consideration, you might determine that there’s nothing: the trinary system of information does not carry enough meaning to make any good calls. That said, we can see a glean a surprising amount of qualitative information from these 25 emojis. Let’s take some samples.

⬛⬛🟩⬛⬛

⬛🟩🟩⬛🟨

Between guess 1 and guess 2, you can assume with a good deal of confidence that I introduced 4 brand new letters in positions 1, 2, 4, and 5.

⬛🟩🟩⬛🟨

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

Here you can assume with decent confidence that the letter which I placed at position 5 in guess 2 ended up at position 1 in guess 3. We can then also assume that 2 new and incorrect letters were introduced.

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Guesses 3 to 5 imply that the first 3 letters of the answer are a relatively common prefix, common enough to cause problems even with 8 (presumably) common letters disqualified. It also lightly implies that the answer is not the first word with this prefix that comes to mind — that it is perhaps a slightly less common word than the previous two guesses. It also may increase the likelihood that the last two letters of the answer are “undesirable” in some way: repeats of green letters, relatively rare letters like Q or Z, etc. This information is probably not enough to make any good guesses, but we can intuit that a person with a lot of time on their hands, or a computer, might be able to find some value.

Now let’s imagine that you, like the people I play Wordle with, know what my starting word is. It’s “SOARE” (a shamefully metagame-y choice). What can you tell now? More than anything, you get a free turn. You now know that, assuming I didn’t change my word, the letters S, O, R, and E are disqualified, and letter 3 is A. That’s enough to give you an advantage, but could you go further? You might assume that I would try other remaining common words like I, O, T, N, M, C, etc. It’s hard because there’s still an extreme amount of entropy here, but remember our second observation about the game: the yellow at position 5 in guess 2 almost certainly moved to position 1 in guess 3. It is relatively rare for a word to begin or end with a vowel (besides ending E’s, which are already disqualified from the previous guess), and the dual placement of this letter on the beginning and end implies that it is most likely a consonant. We have Consonant, X, Vowel, X, X. Very few 5 letter words start with consonant-vowel-vowel, so we can turn down our relative preference for vowels. We could go on like this for some time, but the idea is simple: you cannot pull much certainty from all of the entropy, but you recalibrate your assumptions to get better results in the aggregate. Of course, this would take an immense amount of effort and is borderline cheating, but you could if you wanted to.

You can get the same effect from the opposite direction — if you know the answer, you can determine the likely path or paths someone could take to get there. This is the use case I encountered 6 months ago when I first attempted to make a “reverse solver”. I was making “Wordle Viewer”, the first React project I ever published, and thought the gallery looked weird and empty without word placements. I needed a way to take the results, the answer, and some common starters, and turn it into a feasible list of guesses. This is a bit different from the original premise (how to cheat at wordle), but it is a meaningful step towards it.

My solution initial solution 6 months ago was to take the list of all legal words, order them by their corpus frequency, and then brute-force each result to find the first word that fit the row. For each player, you could input common starting words at the top of this list (For me this would just be “SOARE”). I realized the scope of the challenge when I ran into my first problem — this simplistic algorithm would repeat words. For example, if you take my solution from before

⬛⬛🟩⬛⬛

⬛🟩🟩⬛🟨

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

This algorithm would put “PLACE”, the most common word that fits the restrictions, in row 3 and 4. Humans avoid guessing the same word twice, so this was an immersion-breaker. My solution was just to remove a word from the list whenever it was used. This worked alright for the use-case.

Here’s another example. Imagine that the answer here is “affix”.

⬛🟨🟨⬛⬛

⬛🟨🟨⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

The old algorithm would say give you this reverse solution:

daily

raise

affix

This is a pretty inhuman sequence. A and I are placed in the exact same spot as before! It isn’t representative of how humans would respond to the information they were given. If you continue along their most suggested solutions, you would find a slightly better one.

daily

mixed

affix

This is slightly better because the user isn’t repeating yellows anymore, but there’s still a problem: they dropped the A. While not always the case, human will typically try to place the yellow letters again in new position. The new algorithm gives this solution.

daily

giant

affix

A lot better! Beyond the strangeness of the starting word and the non-attempt at placing an E, this is a realistic version of how a human might play the game.

Now we finally come to the reverse wordle solver: my attempt at redesigning my initial algorithm to generate realistic solutions from human results. I did so using some basic graph theory.

- We use a brute force algorithm to determine for each row, based on the final answer and the row’s colors, every word that could have been guessed. This will naturally include some very rare words, but we order each of these lists by corpus frequency so that common words are prioritized. We can think of each word in these lists as a node on a graph. All nodes on row 1 can go to any nodes on row 2, which can go to any nodes on row 3, etc.

- We run a depth-first search algorithm to find words which naturally follow, based on human play patterns, from the word before. If no word can be found that naturally follows, we try a new word. Because each row’s word list is already ordered by commonality, this prioritizes very common words (it is rare for the first row to have to search past the first few options, but a 4th or 5th row has relatively low viability).

- If we cannot find a path that matches our “human play pattern” standards, we reduce these standards. This is done in 4 phases which are, in the order in which we remove them, all yellow letters are retried, yellow letters are never repeated, blank letters are never reused, and whole words are never repeated.

- If we still can’t find a solution, the given array does not correspond to a real solved wordle

And there you go! This works pretty well, and under very favorable circumstances it does a fantastic job. The presence of yellow squares is the biggest determinant of good results. Yellow squares carry more bits of information than greens or blanks because they tell you where something is and where it isn’t. The second guess of the example wordle, in this case “CLAMP”, was one of only 3 words which have that shape. This is an abnormally low number, and led the reverse solver to accurately determine all of my guesses out of 616,248 possible permutations.

What is this algorithm bad at? Well for one, I still haven’t nailed down a good way of organizing words into a list of desirable and undesirable guesses. A word like “MAMMA” is relatively common, but contains only 2 unique letters. My algorithm would place it above words like “SLATE” or “CRANE”, which are certainly more likely to be guessed by a human. Some metric beyond “how many people know the word” needs to be introduced. How to mesh these two metrics together meaningfully is a tough problem.

I’m now looking ahead to further applications: how can we expand this to the broader goal of cheating at wordle? I can imagine two distinct approaches: a manually calibrated Bayesian algorithm, or a supervised machine learning algorithm. As I write more about this topic, I realize that I need to just make this a 2-parter with no particular deadline. Some quick technical notes

- This was my first meaningful vanilla javascript project. I didn’t mean for it to be — it just expanded a bit from my initial simplistic design which required me to implement some basic DOM manipulation and state logic. It wasn’t difficult, but I definitely could have done it much faster in React or Svelte.

- For the answers list, I’m pirating off of someone else’s website. This site holds the JSON object for each wordle solution in the HTML itself, updated everyday (manually?). I just ask for the index.html, cut away everything that isn’t the object, then JSON.parse(). I’m not sure if this is rude or illegal or whatever. It feels like I’m using a neighbor’s wifi or something.

- It felt good to do a true weekend project. This was the first time I was able to, with relative accuracy, estimate how long something would take.