Today is Friday, the self-imposed deadline for this project. I felt ambitious enough to try to push out an extra feature (in-canvas info tooltips).

I am exhausted. These last 6 weeks have been some of the most productive in my life, but in this last week stretch I’ve been feeling my eyes slowly glaze over. I realized about 3 weeks in that my ambitions for this project would take significantly more time than I thought, and I felt eager to move on to future projects which I believe may fare better. However, I think that it’s important to finish what I start, so I tried to create a polished, minimal product. In the end I think that I’ve made a unique toy that is somewhat technically impressive.

In my previous post I outlined some of my design philosophies and goals surrounding this project. I started my project adhering to these principles pretty closely. About halfway through week 2 I had a working prototype of the game with a basic implementation of the economic simulation. At this time it looked like this:

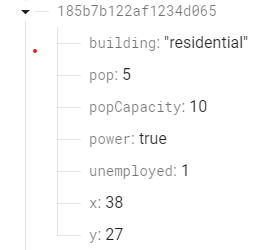

The building objects looked like this under the hood:

This design didn't end up working out, and I lost a good amount of time pursuing it. It's not fully clear at this point whether this was a failure of my design or a failure of my implementation. I think that it's maybe a bit of both -- if the point of choosing a simplified design was to make implementation easier, then difficulty in implementation is at least a partial failure of design. The fundamental problem with the design was that it was incredibly difficult to configure. The economic incentives within each building were simple, but having them interact in a relatively realistic way was difficult. The main problem here was simply setting up market dynamics. With the restriction that everything needed to be incredibly scalable, callable from a serverless function, etc, it was difficult to figure out how to have different buildings "bid for resources". My implementation initially privileged building development (usually a stand in for land value) and distance in the bidding process, but this led to runaway growth from neighborhood power centers that quickly sucked all of the oxygen out of competitors within a few months. More subtle methods of bidding (usually involving some sort of exponential decay in the number of workers/goods available) helped to some degree, but increased configuration complexity to a level which would require a team of developers to maintain.

One idea which I considered but never tried was a stepwise bidding system. In this system, each purchaser would send out signals indicating their desired quantity of goods. Next, the seller would count up the total demand and then send out signals indicating their accepted price function. Lastly, the purchaser would compare neighbors prices and then send out signals indicating their final bid, which would be automatically accepted by all sellers with sufficient inventory. I didn't implement this because it was both computationally expensive and still seemed difficult to configure. Even so, I think that this is the right direction to go in for anyone who might share my interest in this design ethos.

So the old design was a failure because it was too complicated to configure and too computationally expensive to add simplifying oversight mechanisms. In the language of my previous post, my design was too Austrian. I needed a design which was still first and foremost based around distances and neighborhoods, but which considered demand variables in the aggregate instead of on a per-building basis. The solution I came up with was imperfect but decently clever: a road-based heat map for comparative demand.

Here's how this design works:

- Buildings continue to do node searches along roads, but instead of looking for other people they add “heat” values to the road objects it passes along.

- First, each building checks the demand in the adjacent road. It bases its particular supply (and consequently, its demand of input goods and expected consumption of output goods) on this demand. During this stage it may also upgrade or downgrade to a new building level if it has enough resources to do so.

- Next, the building runs a breadth first search along the road network, adding heat values of diminsihing intensity to the roads it passes along. The maximum heat value is determined by the building's supply and demand.

- This ends up with two calculations per buildings, but they are much simpler than before (no more inter-building negotiations) and also would have huge potential for optimization1. The breadth first search sounds bad, but remember that we have a firm maximum distance of 30, so the search is effectively O(1). Even if you have a building surrounded by a 60x60 square of roads, searching through all of them would take less than 50ms. The only concern here is database access time, which could become a problem if you have a few dozen users that want to hurt you.

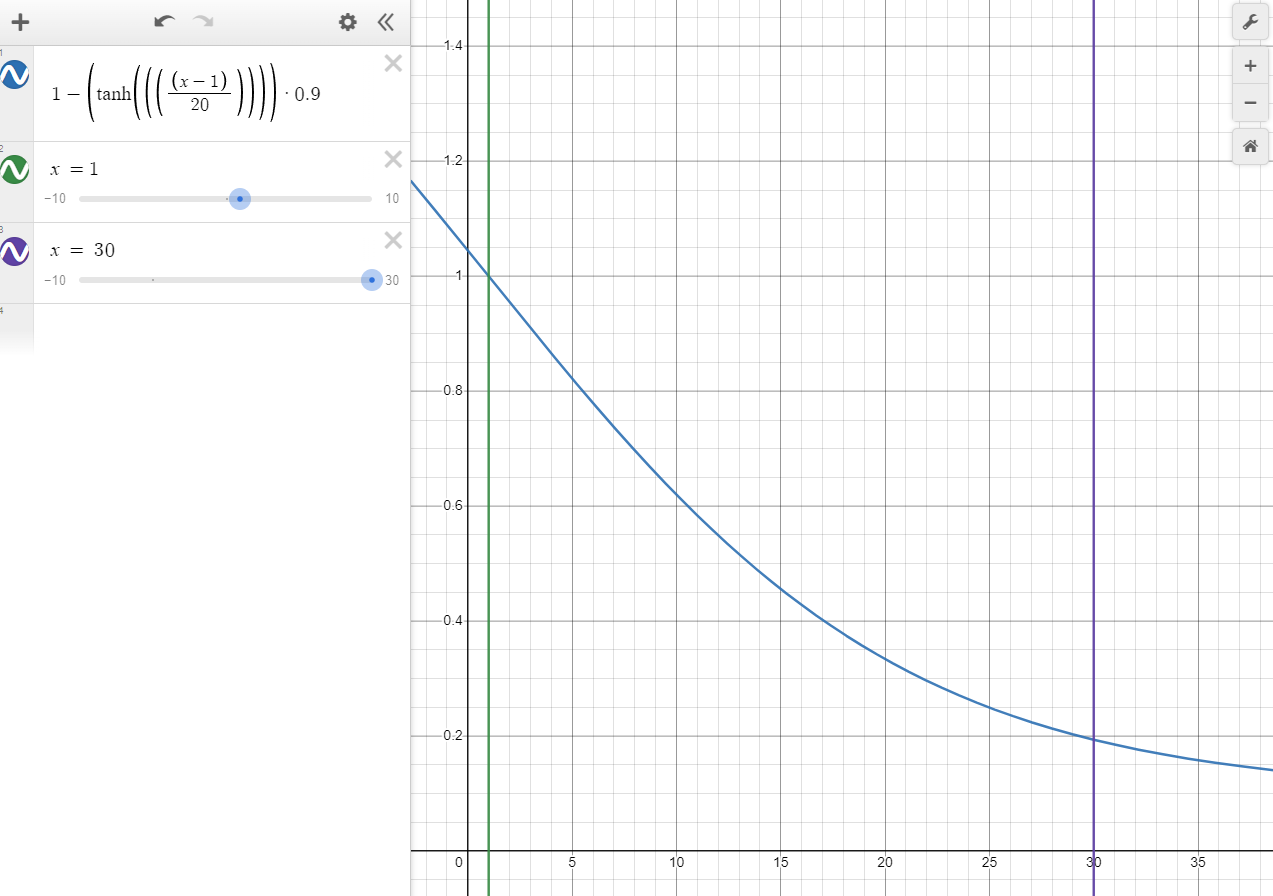

The last thing to do now was configure the heat map. Instead of coming up with some realistic organic figure, I just messed with a sigmoid until it had the shape I was looking for. I wanted strength to be at 100% at x=1 and 20% at x=30 with a limit at 10%

This algorithm continues reasonably after x=30, so we can allow for larger max distances moving forward if we’d like. The quotient at the end can be adjusted to give us a new lower limit (At 0.9 the limit is 10% of the maximum, at 0.8 the limit is 20%, etc.)

This approach works, which makes me happy. It is an economic simulation which is able to use only one-way communication and one economic variable (demand) to simulate a complex economic system. The demand-only approach does have some drawbacks2, but it should keep me within the free tier of GCP even up to a few thousand users, more than I ever expect to have.

This final product does not hit the mark I set out with my original design for a few reasons, but I think it's a good enough product to move on to other things. I still think that the original idea — an economic simulation which focuses on perverse incentives — would be cool to realize. The current implementation of this game has some perverse incentives involved, but nothing that jumps out at the player. I would like to eventually come back to this project in the future and improve on it, but I will be taking a long break from it. If and when I come back to it, I will probably start from near-scratch and spend a lot more time on the design and architecture of the game before putting anything in the code3.

I learned a lot, but I’ve been taking note of the big takeaways I want to remember.

- Premature optimization is fun and project-killing

- I spent probably a combined 2 of the 6 weeks working on components and processes that I ended up dropping or replacing completely. When I first started on this project, I was using DOM elements to render everything. This was incredibly slow and wouldn’t work in the long term, so I delved deep into the inner workings of React to find a way to render 10,000+ DOM elements without dropping frames. It took a week, but I eventually succeeded: a dynamic map of over 10,000 components which could run at 60 fps on low-end hardware. I was incredibly proud of myself. However, I eventually found that adding more advanced graphics to these components was not possible. I had to scrap all of this for an HTML canvas component which I was able to implement in half a day. I learned a lot about how React works from optimizing my DOM display, but the product I was creating served no ultimate purpose. It is better to spend time learning

- Build for the final destination

- This could also be “know where you’re going”. Migrating my project to Firebase took a long, grueling week that sapped me of my energy and forced me to drop features. I read on the firebase docs that you could upload an express server to Google Cloud Functions and thought “awesome, I can just prototype with Node”. A month later I found, to my shock, that uploading my express server to GCF would incur eye-watering costs without complete refactoring. In hindsight this is entirely obvious, how would serverless functions deal with persistent memory? A month ago I pushed that question aside, thinking I would “cross that bridge when I get there”. If I had instead continued research I would have learned that I could emulate firebase functions on my system, allowing me to prototype rapidly without fear of incurring a massive bill.

- Within this project are complicated subsystems that I am incredibly proud of. The unifying feature of all of these is that I had a clear understanding of what I needed them to do and how they would relate to the subsystems around them I started working on them. Many other subsystems in this project have a strong, clean center surrounded by dozens of lines of spaghetti code. These are routines I wrote with tunnel vision – thinking of what I needed to make to get the prototype to work. This is something of an opposite version of premature optimization: rushing initial implementations of code might set you up for a raw deal in the future.

- Productivity drops when I’m not excited

- I accomplished massive feats in the first 3 weeks of this project. After that, once I had delineated what I needed to finish before I could move on to my next project, my productivity saw a steady decline. After the very painful backend migration, my productivity plummeted. I only had ~5 hours of work left, but I was so burnt out and sick of the project that those 5 hours took 7 days. I only managed to finish by setting this deadline for myself. I’ve decided to give myself a few days of a break in the hopes that I can jump into my next project with the same burst of energy that I had at the beginning of this one.

- “Commons” is a shitty name

- When I first came up with the idea for this game, I imagined there would be a lot more interactivity between players. It turns out that system theory is incredibly complex and not something I could calibrate in a month. I’m too exhausted to come up with a new name. Maybe in the theoretical version 2.0 I’ll think of something better

- It’s hard to know when to move on from a project

- I spent half of this project’s 6 weeks in the ‘let’s wrap this up’ phase. If at the 3 week mark I had just dropped the project entirely, would that have been better? What if I took another week to shape what I had into something passable and moved on then? What if I just dropped what I had in my portfolio and labeled it “City builder graphics test”? On the other hand, what if I took an extra month to turn this into something more modern and feature-rich?

- I think I made the right call by finding the couple features I wanted to focus on and finishing those as quickly as I could. The final product is something that I feel comfortable putting in a portfolio, and that was the entire point of the project in the first place.

- This isn’t as much of a “takeaway” as much as an “open question”

-

Remembering the roads you’ve visited to avoid re-exploring the nodes. You would have to start calculating discrete road networks here which would add a lot of your complexity overhead (wouldn't pay for itself until you had 100+ active users). Would need to get clever with storing this information cheaply. Buildings could base heatmap changes on their change in demand so that buildings which are already at equilibrium don't need to do any exploration. Since most buildings in the game are usually at equilibrium, this would probably knock off a good 90% of the computation time. ↩︎

-

More than anything, it is too reliant on "trusting" that the market is behaving normally; it presumes that the market is usually at least close to equilibrium. Whenever the market undergoes a "shock" of some sort, like the rapid destruction or creation of a large number of producing buildings, the market is thrown very quickly out of wack. It takes a good amount of time before the market can re-equilibrate, and in the meantime you get very weird loops of runaway growth and collapse. Basically, any massive shortage or surplus of a good will cause the market to go haywire. When I write this out I realize that this sounds a lot like a normal recessionary or inflationary spiral, but I promise that this is different. It's more like a recessionary or inflationary spiral in a world without a federal reserve, news media, government, or any other kind of oversight — and also every business is run by a 12 year old. ↩︎

-

More than anything, I want to make sure that there is a scrollable infinite canvas view of the world so you can see everything at once. I really hate the fog-of-war approach I had to take here. It's ugly and claustrophobic and confusing. My concern was that this would be too much to download on each page load, but some lazy loading and maybe some server side rendering would probably be able to mitigate this enough to keep it affordable for me and the user. ↩︎